Research Profile

Political participation research has consistently shown that individuals’ socioeconomic position decisively influences their level of participation. For example, average voter turnout declines as respondents’ income situation becomes more precarious (Schäfer 2015). Currently, 16% of the population in Germany is considered at risk of poverty. For a majority of those affected, objectively poor living conditions go hand in hand with subjectively perceived participation deficits and experiences of exclusion (Brettschneider et al. 2020, p. 93ff). Schäfer and Zürn (2021) speak of a “democratic regression”, which cannot be explained solely by socioeconomic or sociocultural factors. Instead, it is also the result of “real representational deficits of liberal democracy,” as politics increasingly prioritises the interests of the wealthy. The literature also describes this as a “democracy of the better‑off” (Kaeding et al. 2015). Moreover, a substantial portion of the population in Germany is formally excluded from voting due to their citizenship status, around eight percent of adults in 2020 (Federal Statistical Office 2020). Despite residing permanently in Germany, their interests are nevertheless systematically neglected in the political process (so‑called *denizens*; see Pedroza 2022).

Political representation of marginalised population groups is therefore also a question of unequal responsiveness in social policy more broadly (for Germany, see Elsässer 2018; Elsässer et al. 2016). These problems are exacerbated by imbalances that exist not only at the individual level but also at the collective level of interest representation. Indeed, organisations that mobilise, aggregate, and represent social interests differ significantly in terms of their ability to advance their cause (Klenk et al. 2022). Overall, the organisation of social interests is marked by a fundamental asymmetry and a strong middle-class bias (von Winter & Willems 2000, p. 10).

The doctoral programme builds on these important diagnoses of democratic deficits and processes of social exclusion, placing the representation of marginalised social groups within current welfare state settings at the centre of its research agenda. Drawing on Wimmer (2023), marginalisation is understood as a process involving substantial disadvantage in at least one of three areas:

- Existential threats – threats to basic livelihood;

- Degradation and stigmatisation;

- Social exclusion – limited participation in economic, social and political life.

Thus, marginalisation is not a static condition but a dynamic process that is continually reproduced through societal norms and institutional structures. Material resources constitute an important, though not solely determining, factor. Particular attention is paid to the intersectionality between specific forms of disadvantage resulting in stigma and materially existential threats (e.g., people with disabilities living in poverty; low‑wage migrant workers; retired persons at risk of old‑age poverty due to care work).

First, the doctoral programme focuses on (potential) beneficiaries of the welfare state, including social work service users (e.g., low-wage earners, families in difficult situations, social assistance recipients) as well as employees in the social services sector (e.g., precarious workers in social service provision). Second, it also turns attention to groups of people (and their potential forms of interest representation) who are entirely excluded from existing systems of provision (e.g., uninsured people or so-called care leavers) or for whom, in many cases, no systems of social protection even exist (e.g., illegalised migrant care workers or unemployed migrants from other EU countries).

The doctoral projects investigate how interests are formed and how they become recognised—or remain unrecognised—through processes of marginalisation, de-marginalisation and privileging, and thereby emerge as weak or strong interests. They also examine how the representation of marginalised interests in the welfare state is pursued and organised, how it is discursively constructed, which instruments are employed, and under which conditions it becomes effective. Accordingly, the doctoral projects address, among other things, the following questions:

- How, and by whom, is a social phenomenon defined as a problem and placed on the political agenda?

- Who is involved in political decision-making and policy formulation in the welfare state, and in which ways?

- Whose interests are reflected in social policies, and in what ways?

- How are marginalised individuals or groups addressed and included in the implementation of policies and social service provision?

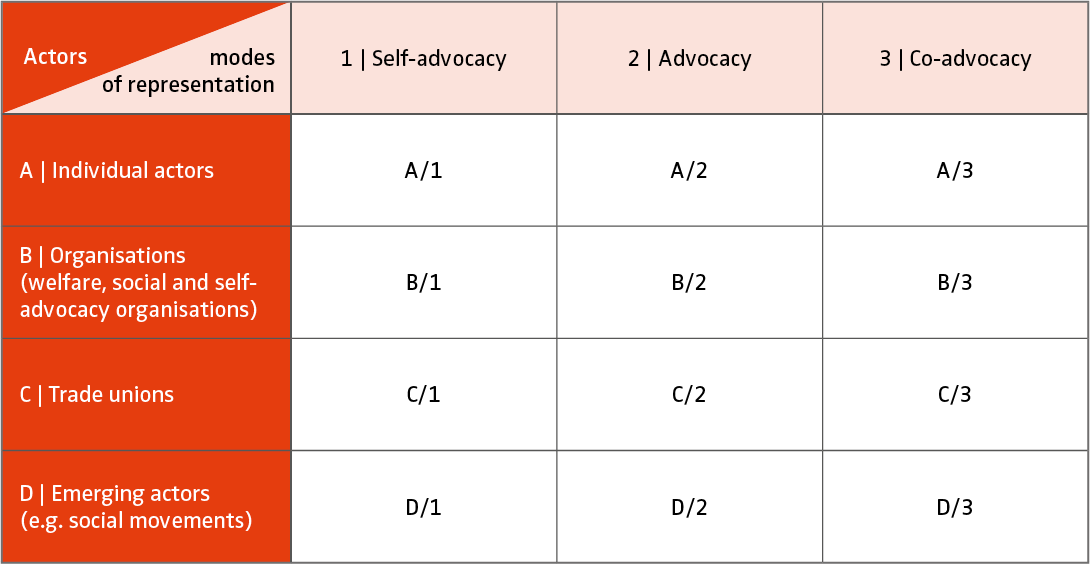

In addition to identifying different actors involved in interest representation, the programme focuses on the following modes of political interest representation, based on analytical distinctions made by Benz (2013) and Ruß (2005):

(1) Advocacy: This refers to advocacy on behalf of marginalised groups, which is usually motivated by socio-political, normative, and religious considerations. This form of representation is considered part of social work actors’ profession as well as some religious and civil society organizations’ activities, such as welfare associations, at various political levels.

(2) Self-advocacy: This refers to the organised, independent articulation and representation of one's own interests by affected groups and their own organisations, manifesting, for examples, in social movements (e.g. “Poor People’s Movements” as described in Piven & Cloward 1977).

(3) Co-advocacy: The basic idea behind this category is that “commercial associations, considered in organisation studies as particularly capable of organising and resolving conflicts, also serve other interests effectively as a by-product of pursuing their own interests” (Ruß 2005, p. 36, free translation). In the context of social policy-making, this primarily refers to trade unions, which represent their members’ interests– in this case, employees – but, due to their distinctive social position, also take other social groups into account.

Analyses also consider tensions and links between these different modes of representation and the rationales underpinning them.

Depending on the topic, the projects thus draw on four different research streams: trade union research, organisation studies focusing on disadvantaged interests, social movement research, and political social work research.

The doctoral projects examine a range of actors and forms of representation of marginalised interests, including diachronic and historical perspectives as well as international comparison.

The research programme is structured around two key aspects: First, a focus on central (individual and collective) actors (Scharpf 2000, pp. 96 ff.), linked to the aforementioned research strands; and second, the modes of interest representation identified above (see Table 1).

Table 1: Thematic structuring of the doctoral program according to actors and modes of interest representation. Own depiction.

Consequently, the dissertation topics are not necessarily distributed evenly across all categories shown in Table 1. Instead, they are to be understood as potential spaces within which connections between the individual dissertations may organically arise.

The doctoral programme adopts a pluralistic approach on theoretical and methodological questions. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed‑methods research designs, as well as diverse epistemological perspectives, are all welcome